How to transform your organization

Find out about the importance of ensuring your people have the tools and resources to do their job, and of making good use of their skills and abilities.

by Jez Humble

Every organization is constantly undergoing change. Therefore, some questions to ask are:

- What is the direction of that change?

- What are the system-level outcomes you are working towards?

- Is the organization better able to discover and serve its customers, and thus achieve its purpose?

- Does the organization’s business model and management of its people provide long-term sustainability?

When it seems as if things aren’t going to plan, it’s common for leaders to roll out a transformation program. However, these programs often fail to achieve their goals, using up large quantities of resources and organizational capacity. This document examines how to successfully execute a transformation and addresses some common sources of failure.

How to implement transformation

There are two key ingredients in effective, ongoing transformation: processes for executing organizational change by setting goals and enabling team experimentation, and mechanisms to spread good practice through the organization.

Set goals and enable team experimentation

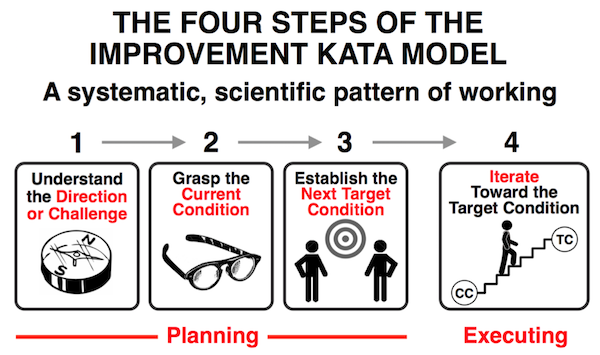

There are many frameworks for executing and measuring organizational change, such as balanced scorecard, objectives and key results (OKRs), and the improvement kata and coaching kata. These frameworks might seem different, but they all share key features. The basic dynamic is shown in the following figure, which is based on the improvement kata framework:

Source: Reproduced by permission of Mike Rother, from Toyota Kata Practice Guide: Practice Scientific Thinking Skills for Superior Results in 20 Minutes a Day by Mike Rother (McGraw-Hill 2018).

All of the frameworks start with a direction (a “true north”) at the organizational or division level. This is an aspirational, system-level business goal set by leadership. It could be an ideal that can’t be achieved, such as zero injuries (the goal chosen by Alcoa’s CEO Paul O’Neill). Or it could be a tough goal that is one to three years out, such as a tenfold increase in productivity (the goal chosen by Gary Gruver, when he was Director of Engineering of HP’s LaserJet Firmware division).

The next step is to understand the current condition. The DORA quick check can help you understand how you’re doing in terms of your software development capabilities and outcomes. Another analysis approach is to perform exercises like value stream mapping, or activity accounting. The point is to understand where the organization is in measurable terms.

The third step is to set measurable targets for a future date. These targets could be described using a format like OKRs, which begin with a qualitative objective, and then specify measurable key results (target conditions). For example, HSBC’s CIO for Global Banking and Markets set every team the goal “to double, half and quarter every year: double the frequency of releases, half the number of low impact incidents, and quarter the number of high impact incidents.”

Finally, teams experiment with ways to achieve these goals until the future date is reached, supported by management. Teams take a scientific approach to experimentation, using the PDCA method (Plan-Do-Check-Act), also known as the Deming cycle. The cycle consists of the following steps:

- Plan: determine the expected outcome.

- Do: perform the experiment.

- Check: study the results.

- Act: decide what to do next.

Teams should be running experiments on a daily basis to try to move towards the target conditions or key results. In the improvement kata, everybody on the team should ask themselves the following five questions every day:

- What is the target condition?

- What is the current condition?

- What obstacles do you think are preventing you from reaching the target condition? Which one are you addressing now?

- What is your next step? What outcome do you expect?

- When can the results be evaluated to see what can be learned from taking that step?

When the results have been captured and new targets are set, repeat the process.

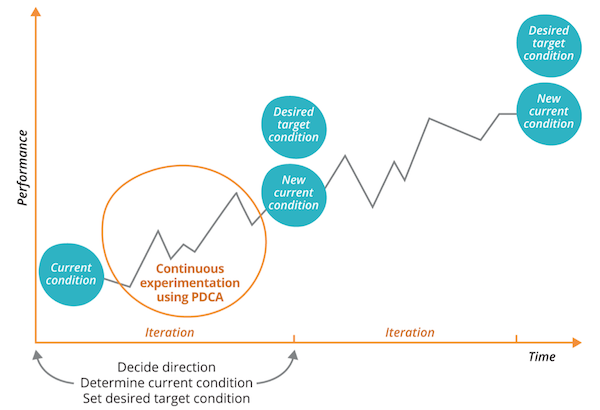

Because the process is performed under conditions of uncertainty, it’s not always clear how the results will be achieved. Therefore, progress is often nonlinear, as shown in the following diagram:

Source: CC-BY: Lean Enterprise: How High Performance Organizations Innovate at Scale by Jez Humble, Joanne Molesky, and Barry O’Reilly (O’Reilly, 2014).

In the planning meetings, participants review the target conditions or key results that were set in the last planning meeting. They then set new goals for the next iteration. In review meetings, participants look at how well the teams are achieving the goals for the iteration and discuss any obstacles and how they will be addressed.

Some important points about this pattern are the following:

- A team’s own target conditions or OKRs must be set by the team. If they are set in a top-down way, teams won’t have a stake in the outcome and thus won’t be as invested in achieving them. Instead, the team might “game” them—that is, manipulate the outcome to meet the goal artificially.

- It’s acceptable to not achieve the goals; some of the goals are stretch goals, meaning that they’re purposely designed to be challenging. Teams should expect to achieve about 80% of the goals. It’s common when starting with cultural transformation to not achieve any of the specified goals. If this happens, the team needs to set a single goal for the next iteration and dedicate everything to achieving it.

- Many goals and measures will change from iteration to iteration as the team’s goals and current conditions change, and as they learn through working towards their goals. Don’t spend too much time trying to set the perfect objectives: focus on executing the process so you can start learning.

- It’s important for teams to have the necessary autonomy, capacity, resources, and management and leadership support to do improvement work. Teams should not let the normal delivery work crowd out improvement work, because the improvement work is what will help fix the inefficiencies that make it so slow to deliver products and services.

Build community structures to spread knowledge

After teams have discovered better ways of working, the next task is to spread lessons learned throughout the organization. There are many ways to do this. In the 2019 State of DevOps Report researchers asked respondents to share how their teams and organizations spread DevOps and Agile methods by selecting from one or more of the following approaches (see Appendix B of the 2019 State of DevOps Report for detailed descriptions):

- Training center (sometimes referred to as a dojo)

- Center of excellence (CoE)

- Proof of concept (PoC) but stall

- Proof of concept as a template

- Proof of concept as a seed

- Communities of practice

- Big bang

- Bottom-up or grassroots

- Mashup

Analysis shows that high performers favor strategies that create community structures at both low and high levels in the organization, likely making them more sustainable and resilient to re-organizations and product changes. The top two strategies employed are communities of practice and grassroots, followed by proof of concept as a template (a pattern where the proof of concept gets reproduced elsewhere in the organization), and proof of concept as a seed. For an example of how a community of practice works, read about how Google’s culture of comprehensive unit testing was driven by a group of volunteers.

Low performers tend to favor training centers and centers of excellence: strategies that create more silos and isolated expertise. They also attempt proofs of concept, but these generally stall and don’t see success. Why might these strategies fail to deliver effective change?

By centralizing expertise in one group, centers of excellence create several problems. First, the CoE is now a bottleneck for the relevant expertise for the organization and this cannot scale as demand for expertise in the organization grows. Second, it establishes an exclusive group of “experts” in the organization, in contrast to an inclusive group of peers who can continue to learn and grow together. This exclusivity can chip away at healthy organizational cultures. Finally, the experts are removed from doing the work. They are able to make recommendations or establish generic “best practices” but the path from the generic learning to the implementation of real work is left up to the learners. For example, experts will build a workshop on how to containerize an application, but they rarely or never actually containerize applications. This disconnect between theory and hands-on practice will eventually threaten their expertise.

While some see success in training centers, they require dedicated resources and programs to execute both the original program and sustained learning. Many companies have set aside incredible resources to make their training programs effective: They have entire buildings dedicated to a separate, creative environment, and staff devoted to creating training materials and assessing progress. Additional resources are then needed to assure that the learning is sustained and propagated throughout the organization. The organization has to provide support for the teams that attended the training center, to help ensure their skills and habits are continued back in their regular work environments, and that old work patterns aren’t resumed. If these resources aren’t in place, organizations risk all of their investments going to waste. Instead of a center where teams go to learn new technologies and processes to spread to the rest of the organization, new habits stay in the center, creating another silo, albeit a temporary one. There are also similar limitations as in the CoE: If only the training center staff (or other, detached “experts”) are creating workshops and training materials, what happens if they never actually do the work?

Mashups were commonly reported (40% of the people responding to the 2019 survey used this strategy), but they lack sufficient funding and resources in any particular investment. Without a strategy to guide a technology transformation, organizations will often make the mistake of hedging their bets and suffer from death by initiative: identifying initiatives in too many areas, which ultimately leads to under-resourcing important work and dooming them all to failure. Instead, it is best to select a few initiatives and dedicate ongoing resources to ensure their success (time, money, and executive and champion practitioner sponsorship). In contrast to mashups, very few people report use of a big bang strategy, although it was most common in low performers.

Additional analysis identified four patterns used by high performers, ordered by prevalence:

- Community builders: This group focuses on communities of practice, grassroots, and proofs of concept (as a template and as a seed, as described earlier). This occurs 46% of the time.

- Emergent: This group has focused on grassroots efforts and communities of practice. This appears to be the most hands-off group and appears in 23% of cases.

- Experimenters: Experimenters appeared in 22% of cases. This group has high levels of activity in all strategies except big bang and dojos—that is, all activities that focus on community and creation. They also include high levels in PoCs that stall. The fact they are able to leverage this activity and remain high performers suggests they use this strategy to experiment and test out ideas quickly.

- University: This group focuses on education and training, with the majority of their efforts going into centers of excellence, communities of practice, and training centers. This pattern was only observed 9% of the time, suggesting that while this strategy can be successful, it is not common and requires significant investment and planning to ensure that lessons learned are scaled throughout the organization.

Principles of effective organizational change management

All organizations are complex, and every organization has different goals, a different starting point, and their own ways of approaching challenges. Prescriptions that work in one organization might not show the same results in another organization. However, your organization can follow some general principles in order to increase your chances of success.

Improvement work is never done

High-performing organizations are never satisfied with their performance and are always trying to get better at what they do. Improvement work is ongoing and baked into the daily work of teams. People in these organizations understand that failing to change is as risky as change, and they don’t use “that’s the way we’ve always done it” as a justification for resisting change. However that doesn’t mean taking an undisciplined approach to change. Change management should be performed in a scientific way in pursuit of a measurable team or organizational goal.

Leaders and teams agree on and communicate measurable outcomes, and teams determine how to achieve them

It’s essential that everybody in the organization knows the measurable business and organizational outcomes that they are working towards. These outcomes should be short (a few sentences at most) at the organizational level, and match up clearly to the purpose and mission of the organization. At the level of an individual business unit, the outcomes should fit on a single page. The organizational outcomes should be decided by leaders and teams working together, although leaders have the ultimate authority. At lower levels of the organization, goals are stated in more detail and with shorter horizons.

However, it should be up to teams to decide how they go about achieving these outcomes, for these reasons:

- Under conditions of uncertainty, it’s impossible to decide the best course of action through planning alone. That doesn’t mean some level of planning isn’t important. But teams should be prepared to alter or even rewrite the plan based on what they discover when trying to execute it.

- When people are told both what to do and how to do it, they lose their autonomy and a chance to harness their ingenuity. Not only does this produce worse outcomes, it also leads to disengaged employees.

- Problem-solving is critical in helping employees develop new skills and capabilities. Organizations should give teams problems to solve, not tasks to execute.

Large-scale change is achieved iteratively and incrementally

The annual budgeting cycle tends to drive organizations towards a project-based model in which work of all kinds is tied to expensive projects that take a long time to deliver. With few exceptions, it’s better to break work down into smaller pieces that can be delivered incrementally. Working in small batches delivers a host of benefits. The most important is that it lets organizations correct course based on what they discover. This avoids wasting time and money doing work that doesn’t deliver the expected benefits.

Moving from a project paradigm to the product paradigm is a long-term trend that will take most industries years to execute, but it’s clear that this is the future. Even the US federal government has successfully experimented with modular contracting to pursue a more iterative, incremental approach to delivering large pieces of work.

The issues that apply to delivering projects also apply to transformation. Organizations should find ways to achieve quick wins, share learning, and help other teams experiment with these new ideas.

Common pitfalls in transforming culture

Leaders often make the following mistakes when they attempt to make large-scale changes to an organization.

-

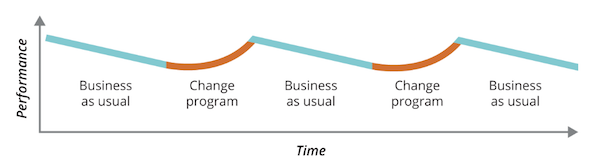

Treating transformation as a one-time project. in high-performing organizations, getting better is an ongoing effort and part of everybody’s daily work. However, many transformation programs are treated as large-scale, one-time events in which everyone is expected to rapidly change the way they work and then continue on with business as usual. Teams are not given the capacity, resources, or authority to improve the way they work, and their performance gradually degrades as the team’s processes, skills and capabilities become an ever poorer fit for the evolving reality of the work. You should think of technology transformation as an important value-delivery part of the business, one that you won’t stop investing in. After all, do you plan to stop investing in customer acquisition or customer support?

-

Treating transformation as a top-down effort. In this model, organizational reporting lines are changed, teams are moved around or restructured, and new processes are implemented. Often, the people who are affected are given little control of the changes and are not given opportunities for input. This can cause stress and lost productivity as people learn new ways of working, often while they are still delivering on existing commitments. When combined with the poor communication that is frequent in transformation initiatives, the top-down approach can lead to employees becoming unhappy and disengaged. It’s also uncommon for the team that’s planning and executing the top-down transformation to gather feedback on the effects of their work and to make changes accordingly. Instead, the plan is executed regardless of the consequences.

-

Failing to agree on and communicate the intended outcome. Transformations are sometimes executed with poorly defined goals, or with qualitative (rather than quantitative) goals, such as “faster time-to-market” or “lower costs.” Sometimes goals are defined but are not achievable, or the goals pit one part of the organization against the other. In these cases, it’s impossible to know whether the improvement work is having the intended effect. When this failure is combined with a top-down approach, it becomes hard to experiment with other approaches that might be faster or cheaper. The result is typically waste when the plan is executed, and an inability to determine whether the goal was achieved or the program worked. In many cases, instead of the failure being critically analyzed and used as a learning opportunity, the failure is ignored and new wholesale change initiative is started or entire methodologies are discredited.

The combination of treating transformation as a project and treating it as a top-down initiative tends to lead to the pattern shown in the following diagram. Performance gradually degrades. At the start of a transformation program, it initially gets worse before improving. But then this is followed by a transition back to business as usual. All the while, cynicism and disengagement increases across the organization.

Source: CC-BY: Lean Enterprise: How High Performance Organizations Innovate at Scale by Jez Humble, Joanne Molesky, and Barry O’Reilly (O’Reilly, 2014).

What’s next

- Explore our DevOps research program.

- Take the DORA quick check to learn where you stand and identify opportunities for improvement